By Hannah Landel ’22 and Abby Nicholson ’23

Introduction

After nearly two decades of military conflict in Afghanistan, the August 2021 withdrawal caused mixed feelings among American citizens and legislators alike. While many were relieved to see the end of the war, others feared for the future of Afghan women and girls under Taliban rule. This concern is not new and has been a part of the discussion about the war since the beginning; in 2003, First Lady Laura Bush famously declared: “The fight against terrorism is also a fight for the rights and dignity of women.”[1] Likewise, political scientist Sara Angevine concludes that female legislators have a particular interest in the conditions of women abroad. She finds that being a woman significantly increases the likelihood of sponsoring bills related to foreign policy affecting women; thus, American women in Congress “appear to be acting as global surrogates for women worldwide.”[2] In order to understand how Angevine’s findings relate to congressional discussions of the withdrawal and to analyze which factors make a committee member more likely to mention girls and women in the context of the Afghanistan withdrawal, we examine the proportion of committee members that mention women and girls in their statements in various committee hearings by analyzing data collected from Senate Armed Services Committee hearings from May 20 and September 28, 2021, and from Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearings from April 27 and September 14, 2021. We consider the following variables: sex, party, committee membership, and timing, meaning whether the statement was given during a hearing that took place pre- or post-withdrawal.

Quantitative Analysis

Using data collected on the issues mentioned in Senate Armed Services and Foreign Relations hearings both pre- and post-withdrawal, we graph the proportion of committee members who mentioned women and girls in their statements by sex, party, committee, and hearing timing. We define mentioning women and girls as an explicit mention of women or girls in Afghanistan in any one of a member’s statements within each committee hearing.

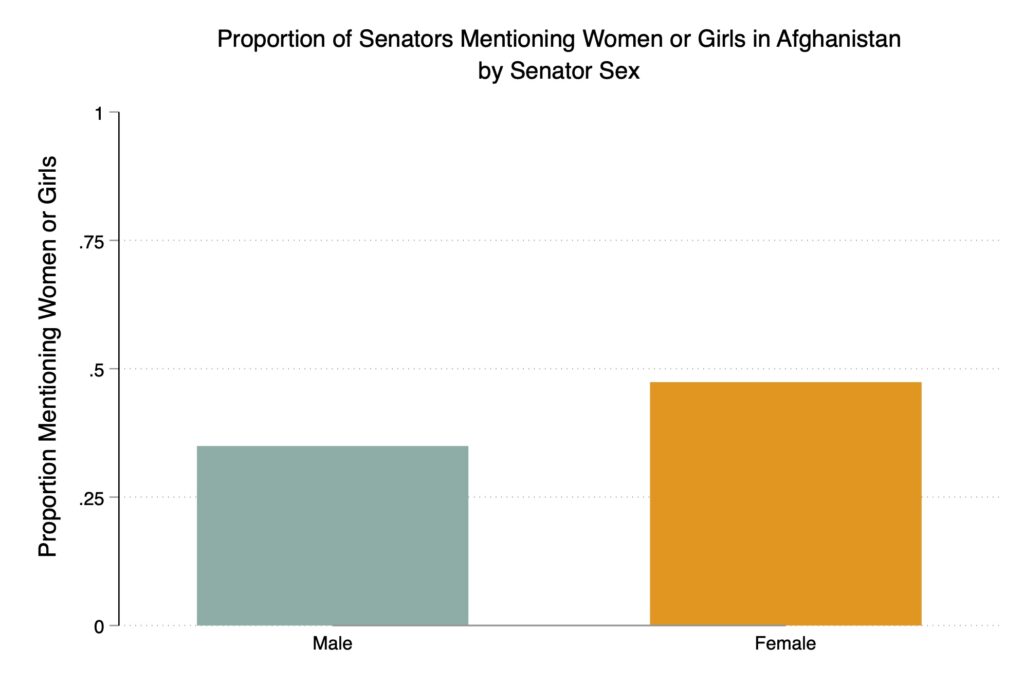

We begin by graphing the proportion of committee members who mention women and girls by sex of committee member (see Figure 1). We find that female legislators are more likely to mention women and girls in their statements than men; while 35% of male committee members mentioned women and girls in at least one of their statements, 47% of female committee members mentioned women and girls in at least one of their statements. As women themselves, female legislators could be more likely to mention girls and women in the context of the withdrawal from Afghanistan because they feel that they have a shared experience with women everywhere and feel the need to advocate for other women. This is in line with Angevine’s findings that female legislators often act as “global surrogates for women worldwide.”[3]

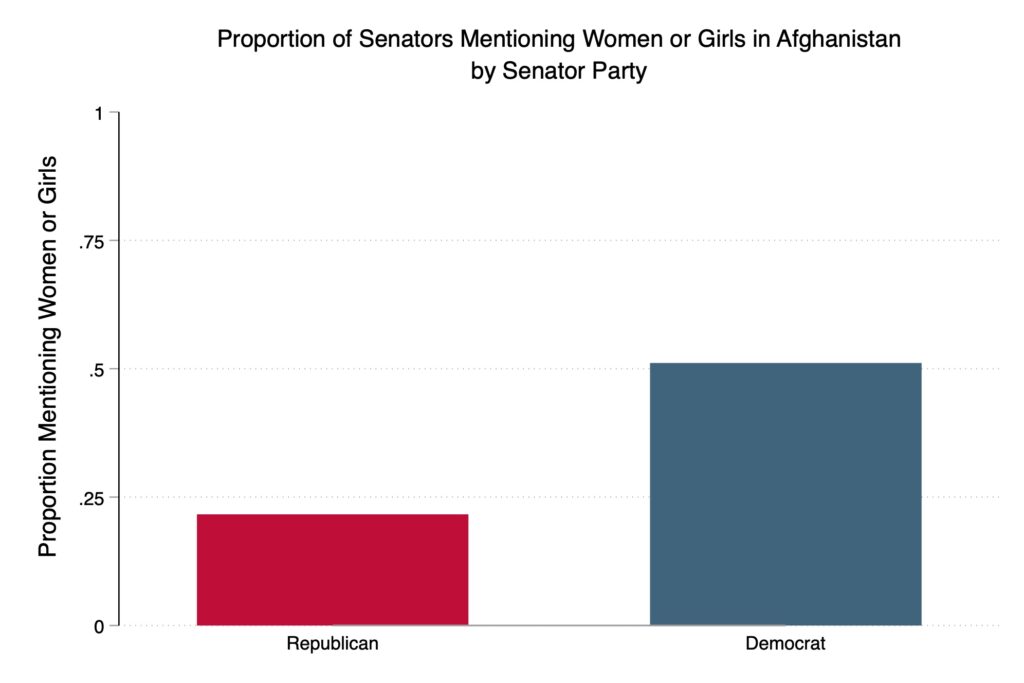

Next, Figure 2 graphs the proportion of committee members who mention women and girls by the party affiliation of each committee member. Democrats were more than twice as likely to mention women and girls than Republicans, with 51% of Democrats mentioning women and girls in at least one of their statements and only 22% of Republicans doing so. Since Democrats tend to be the ones who focus on women’s issues and more specifically work to protect women’s rights (think of Democrats protecting women’s bodily autonomy with their pro-choice stance on abortion), it makes sense the Democrats are also the ones more likely to worry about the safety of women and girls in Afghanistan.

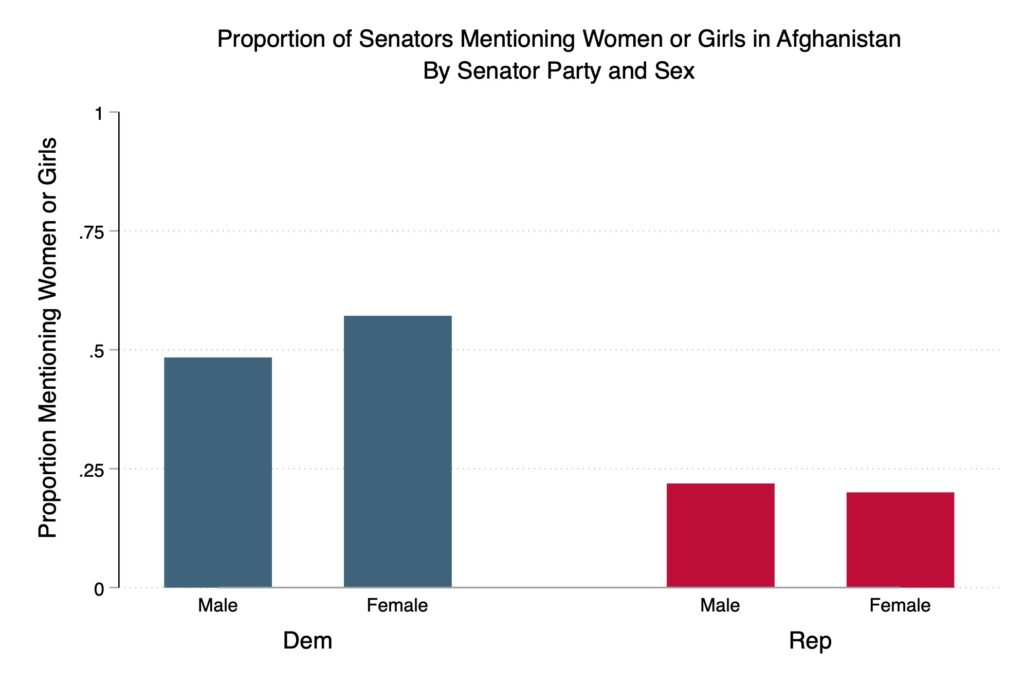

Figure 3 further breaks down the proportion of Democrats and Republicans who mentioned women and girls in their congressional hearing statements by sex. While Democratic women were more likely to mention women and girls in their statements than Democratic men, Republican men were more likely to mention women and girls than Republican women. Additionally, the difference between male and female mentions is larger with Democrats than Republicans — 48% of male Democrats mentioned women and girls while 57% of female Democrats did so, and 22% of male Republicans mentioned women and girls while 20% of female Republicans did so.

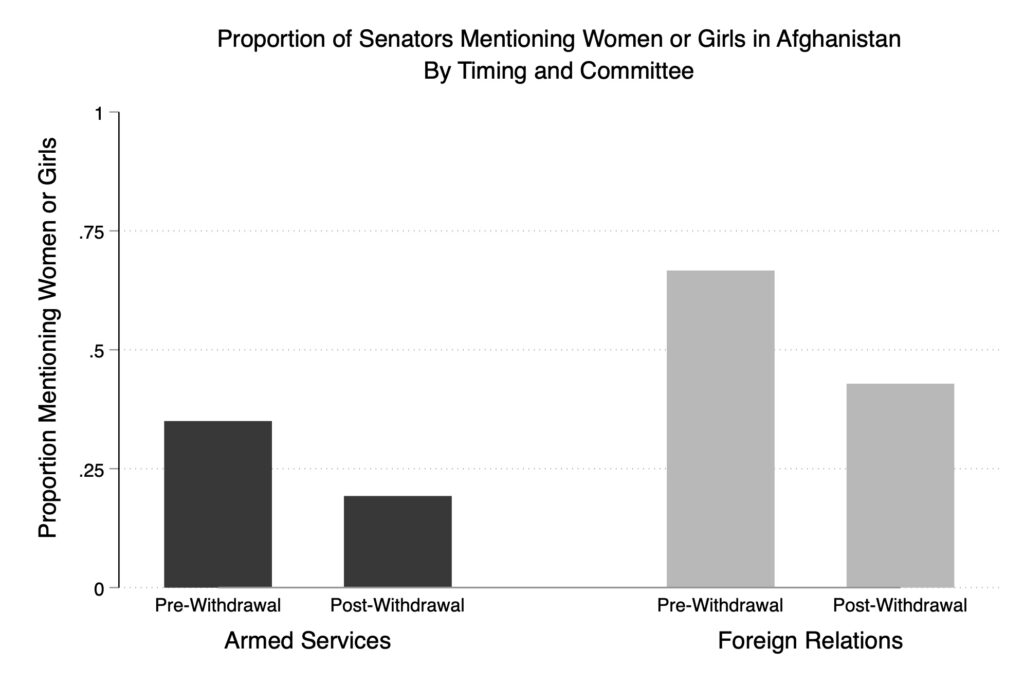

Figure 4 depicts the proportion of committee members who mention women and girls by the committee each member belongs to, as well as by the timing of the statement (pre- or post-withdrawal). Overall, 35% of Armed Services Committee members mentioned women and girls before the withdrawal while 19% did so after the withdrawal. By comparison, 67% of Foreign Relations Committee members mentioned women and girls before the withdrawal and 43% did so post-withdrawal. Across the board, members of the Foreign Relations Committee were more likely to mention women and girls than members of the Armed Services Committee. One possible explanation is that because the jurisdiction of the Foreign Relations Committee encompasses humanitarian aid and other humanitarian considerations,[4] Foreign Relations Committee members are more likely to mention the safety of women and girls in Afghanistan relative to the Armed Services Committee, which deals more primarily with defense issues.[5]Interestingly, in both committees, women and girls were mentioned more often before the withdrawal compared to after. While it is unclear why this is the case, it could be that the safety of women and girls in Afghanistan was a bigger question in the lead-up to the withdrawal in terms of strategy and possible points of regression should the Taliban take over should the United States withdraw than after the withdrawal, when most of the backlash was centered around the rapidity with which the Taliban took over and the safety of both citizens and Afghan allies left behind.

Qualitative Analysis

In addition to measuring the number of mentions of women and girls across several variables, we are interested in examining the content of such statements. Overall, women and girls were most commonly referenced regarding concerns about their rights to education, safety, and self-expression during the withdrawal and a possible Taliban reign. However, while the issue seems to be included as part of the US policy agenda for ensuring a smooth transition, there is less discussion of women and girls after the withdrawal. When women and girls were mentioned in September, the focus seems to be mainly on protecting them from immediate violence from the Taliban as opposed to maintaining the rights and freedoms that were previously mentioned. Senator Schatz (D-HI), for example, expressed concern, stating: “I am worried about reports that we are seeing about acts of violence against journalists, women, and girls.”[6]

While there were many concerns expressed by Congress members regarding the withdrawal, the issue of women’s rights and security was particularly salient for Senator Shaheen (D-NH). Her statement on April 27 in the Foreign Relations Committee was almost entirely dedicated to discussing this topic. In her speech, she mainly describes the violence experienced by Afghan women, citing the need to ensure their “basic human rights.” Later, in the September 14 committee hearing, Shaheen says: “And I have to say over the last 20 years, we have made a difference, collectively, in Afghanistan. And possibly the biggest difference we made was for women and girls. Access to education, access to healthcare, access to work and opportunity. All of that was as a result of many of the efforts that we made and that this Congress made and supported, including with very, very significant assistance.”[7] This statement as well as her previous statement suggests that for Democrat women like Shaheen, the fate of women and girls is of particular importance. This supports Angevine’s findings about female legislators acting as global surrogates for women abroad.

Conclusion

Since the beginning of the war in Afghanistan in 2001, the future of Afghan women and girls under Taliban rule has been an issue of concern. To examine the congressional response to the safety of Afghan women and children after US withdrawal from Afghanistan, we graph the proportion of committee members who mentioned women and girls in the Armed Services Committee hearings from May 20 and September 28, 2021, and from the Foreign Relations Committee hearings from April 27 and September 14, 2021, by sex, party, committee, and timing. We find that female committee members, Democrats, and Foreign Relations committee members were more likely to mention Afghan women and girls in their statements. Additionally, committee members were more likely to mention women and girls prior to the withdrawal. When committee members did mention women and girls, they tended to talk about women’s and girls’ right to safety, self-expression, and education. Future work should examine legislators more generally using concerns for the safety of women and girls as justification for military engagement, especially from a human rights advocacy standpoint.

[1] Abu-Lughod, Lila. “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others.” American Anthropologist 104, no. 3 (2002): 784. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3567256.

[2] Angevine, Sara. “Representing All Women: An Analysis of Congress, Foreign Policy, and the Boundaries of Women’s Surrogate Representation.” Political Research Quarterly 70, no. 1 (2017): 98–110. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26384903.

[3] Angevine (2017)

[4] https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/117th_rules_US_senate_foreign_relations_committee.pdf

[5] https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/about/history

[6] Senator Schatz, “Examining The U.S. Withdrawal From Afghanistan,” 9/14/21, U.S. Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, Washington, DC.

[7] Senator Shaheen, “Examining The U.S. Withdrawal From Afghanistan,” 9/14/21, U.S. Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, Washington, DC.